Quality issues have been of great concern throughout the recorded history of human beings. During the New Stone Age, several civilizations emerged, and some 4000–5000 ago, considerable skills in construction had been acquired. The pyramids in Egypt were built approximately during 2589–2566 BC. The king of Babylonia (1792–1750 BCE) had copied the law, and according to which, during the Mesopotamian era, builders were responsible for maintaining the quality of buildings and were given the death penalty if any of their constructed buildings collapsed and its occupants were killed. Records exist to show that the extension of Greek settlements around the Mediterranean after 200 BCE featured temples and theatres were built using marble. India had strict standards for working in gold in the fourth century BCE.

During the middle Ages, guilds took the responsibilities for quality control upon themselves. Guilds and governments carried out quality control while consumers carried out informal quality inspection during every age of humanity.

The guilds’ involvement in quality was extensive. All craftsmen living in a particular area were required to join the corresponding guild and were responsible for controlling the quality of their own products. If any of the items was found defective, then the craftsman was forced to discard the faulty items. The guilds also punished members who turned out shoddy products. Guilds maintained inspections and audits to ensure that artisans followed the quality specifications. Guild hierarchy consisted of three categories of workers: apprentice, the journeyman, and the master. Guilds had established specifications for input materials, manufacturing processes, and finished products, as well as methods of inspection and test. Guilds were active in managing the quality during Middle Ages until the Industrial Revolution reduced their influence.

The Industrial Revolution began in Europe in the mid-eighteenth century and gave birth to factories. The goals of the factories were to increase productivity and reduce costs. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, items were produced by individual craftsman for individual customers, and it was possible for workers to control the quality of their own products. Working conditions then were more conducive for professional pride. Under the factory system, the tasks needed to produce a product were divided up among several or many factory workers. In this system, large groups of workmen performed a similar type of work, and each group worked under the supervision of a foreman who also took on the responsibility to control the quality of the work performed. Quality in the factory system was ensured through skilled workers, and the quality audit was done by inspectors.

The broad economic result of the factory system was mass production at low cost. The Industrial Revolution changed the situation dramatically with the introduction of this new approach to manufacturing. In the early nineteenth century, the approach to manufacturing in the United States tended to follow the craftsmanship model used in the European countries. In the late nineteenth century, Fredrick Taylor’s system of Scientific Management was born. Taylor’s goal was to increase production. He achieved this by assigning planning to specialized engineers, and the execution of the job was left to the supervisors and workers. Taylor’s emphasis on increasing production had a negative effect on quality. With this change in the production method, inspection of finished goods became the norm rather than inspection at every stage. To remedy the quality decline, factory managers created inspection departments having their own functional bosses. These departments were known as quality control departments.

The beginning of the twentieth century marked the inclusion of process in quality practices. During World War I, the manufacturing process became more complex. Production quality was the responsibility of quality control departments. The introduction of mass production and piecework created quality problems, as workmen were interested in increasing their earnings by producing more, which in turn led to bad workmanship. This led factories to introduce full-time quality inspectors, which marked the real beginning of inspection quality control and thus the beginning of quality control departments headed by superintendents. Walter Shewhart introduced statistical quality control in processes. His concept was that quality is not relevant for the finished product, but for the process that created the product. Shewhart’s approach to quality was based on continuous monitoring of process variation. The statistical quality control concept freed the manufacturer from a time-consuming 100% quality control system because it accepted that variation is tolerable up to certain control limits. Thus quality control focus shifted from the end of the line to the process.

The systematic approach to quality in industrial manufacturing started during the 1930s when the cost of scrap and rework attracted attention. With the impact of mass production, which was required during World War II, it became necessary for manufacturing units to introduce a more stringent form of quality control. Called Statistical Quality Control (SQC), SQC made a significant contribution in that it provided a sampling inspection rather than a comprehensive inspection. This type of inspection, however, did lead to a lack of realization of the importance of engineering to product quality.

The concept and techniques of modern quality control were introduced in Japan immediately after World War II. The statistical and mathematical techniques, sampling tables, and process control charts emerged during this period.

From the early 1950s to the late 1960s, quality control evolved into quality assurance, with its emphasis on problem avoidance rather than problem detection. The quality assurance perspective suffered from a number of shortcomings as its focus was internal. Quality assurance was generally limited to those activities that were directly under the control of the organization; important activities such as transportation, storage, installation, and service were typically either ignored or given little attention. The quality assurance concept pays little or no attention to the competition’s offerings. This resulted in integration of the quality actions on a companywide and application of quality principles in all the areas of business from design to delivery instead of confining the quality activities to production activities. This concept was called Total Quality Control and was popularized by Armand V. Feigenbaum, a quality guru from the United States.

From the foregoing brief overview and many other writings about the history of quality, it is evident that the quality system in its different forms has moved through distinct quality eras such as:

- Quality Inspection

- Quality Control

- Quality Assurance

- Total Quality

Introduction and promotion of companywide quality control led to a revolution in management philosophy. To help sell their products in international markets, the Japanese took some revolutionary steps to improve quality:

- Upper-level managers personally took charge of leading the revolution.

- All levels and functions received training in the quality disciplines.

- Quality improvement projects were undertaken on a continuing basis at a revolutionary pace.

Thus, the concept of quality management started after Word War II, broadening into the development of initiatives that attempted to engage all employees in the systematic effort for quality. Quality emerged as a dominant thinking, becoming an integral part of an overall business system focused on customer satisfaction, which became known as Total Quality Management (TQM), with its three constitutive elements:

- Total: Organizationwide

- Quality: Customer Satisfaction

- Management: Systems of Managing.

TQM was stimulated by the need to compete in the global market, where higher quality, lower cost, and more rapid development are essential to market leadership. TQM was/is considered to be a fundamental requirement for any organization to compete, let alone lead its market. It is a way of planning, organizing, and understanding each activity of the process and removing all the unnecessary steps routinely followed in an organization. TQM is a philosophy that makes quality values the driving force behind leadership, design, planning, and improvement in activities. It acknowledges quality as a strategic objective and focuses on continuous improvement of products’ processes, services, and cost, to compete in the global market by minimizing rework and maximizing profitability to achieve market leadership and customer satisfaction. It is a way of managing people and business processes to ensure customer satisfaction. TQM involves everyone in the organization in the effort to increase customer satisfaction and achieve superior performance of the products or services through continuous quality improvement. TQM helps in the following:

- Achieving customer satisfaction

- Continuous improvement

- Developing teamwork

- Establishing a vision for the employees

- Setting standards and goals for the employees

- Building motivation within the organization

- Developing a corporate culture

The TQM approach was developed immediately after World War II. There are prominent researchers and practitioners whose works have dominated the quality movement. Their ideas, concepts, and approaches in addressing specific quality issues have become part of the accepted wisdom in the field of quality, resulting in a major and lasting impact on the business. These persons are known as quality gurus. They all emphasize involvement of organizational management in quality efforts. These philosophers (gurus) are:

- Philip B. Crosby

- W. Edwards Deming

- Armand V. Feigenbaum

- Kaoru Ishikawa

- Joseph M. Juran

- John Oakland

- Shigeo Shingo

- Genichi Taguchi

Their approaches to quality emphasize customer satisfaction, management leadership, teamwork, continuous improvement, and minimizing defects. The common features of their philosophies can be summarized as follows:

- Quality is conformance to the customer’s defined needs.

- Senior management is responsible for quality.

- Continuously improve process, product, and services through application of various tools and procedures to achieve a higher level of quality.

- Establish performance measurement standards to avoid defects.

- Take a team approach by involving every member of the organization.

- Provide training and education for everyone in the organization.

- Establish leadership to help employees perform a better job.

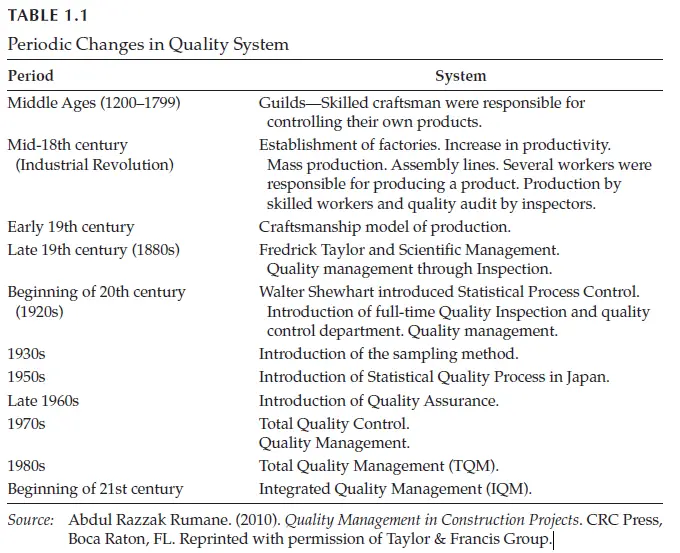

TQM was considered a fundamental requirement for any industry to compete, let alone lead, in its market. The TQM methods were used until the end of the twentieth century. The concept and culture of the Integrated Quality Management System (IQM) emerged at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The IQM system integrates all the relevant systems in it for competitive advantages. Below table summarizes periodic changes in quality systems and the birth of IQMs.

Source: Abdul Razzak Rumane, Quality Tools For Managing Construction Projects.